Theoretical Rescue Mission For The Columbia Space Shuttle - Part Two of Two Parts

Part Two of Two Parts (Please read Part One first)

In contrast to the frantic activity preparing the Atlantis and the astronauts on the ground, there would have been little to do on the Columbia. Following EVA to check on the wing damage and make preparations to move to the Atlantis, the only other preparations would be to maneuver the Columbia into an upside down orbital orientation with the tail pointed in the direction of flight. This would require minimum expenditure of propellant. For the crew of the Columbia, the stress of inactivity while waiting for rescue by the Atlantis would have been difficult to endure. They would not even be able to watch what was happening because all cameras and television equipment would be shut down to conserve power.

The International Space Station was in orbit around the Earth. The question could be raised of why the Columbia didn't rendezvous and dock with the ISS where the crew could find refuge. Unfortunately, the Columbia only had a tiny fraction of the fuel that would have been required to carry out the necessary change of orbit to rendezvous with the ISS.

A major concern about a possible rescue mission by the Atlantis had to do with what had happened to the Columbia. Foam had broken off the same place on previous space shuttles at least six times before the Columbia was launched. Once it was establish that such detached foam could fatally damage the integrity of a shuttle, the question had to be asked, "What if we launched the Atlantis on a rescue mission and a piece of foam broke off and seriously damaged the Atlantis too? Is that a risk worth taking to rescue the crew of the Columbia? There was no time to redo the foam insulation on the external tank for the Atlantis.

There were three days in mid-February that could have provided launch windows for a rescue mission. One big concern about scheduling launches is weather. The weather has to be calm not just for the launch itself but also for possible emergency landing sites in case the mission had to be aborted. Records show that the three days in question had clear weather forecasts. However, all three launch windows were at night which would make it much more difficult to assess possible foam damage to wing tiles of the Atlantis after launch.

If the Atlantis was successfully launched it would have approached straight up below the Columbia. The Atlantis would approach within twenty feet of the Columbia at right angles to the Columbia to prevent their tails from colliding. The two pilots would trade off holding the Atlantis steady with respect to the Columbia for the estimated nine hours of the transfer.

The bays of both shuttles would be opened and the two EVA crew members would begin to move the crew of the Columbia to the Atlantis. Two space suits would have to be recycled which is what would make the transfer operation last so long. Putting on space suits and taking them off is a difficult and time consuming operation. The last two crew to leave the Columbia would make final preparations for ground control to deorbit the Columbia. The combined crews of the two shuttles would strap in and, hopefully, successfully land back on Earth.

Such a rescue mission would have been extremely difficult but might have succeeded if we had known about the problem with the shattered tile soon enough. After the CAIB report was issued and the shuttles flew again, a new protocol was put into place. With the first launch in 2005 after the grounding of the fleet, no shuttle ever flew again without a rescue shuttle standing by, ready to launch in case there was a problem. Fortunately they were never needed.

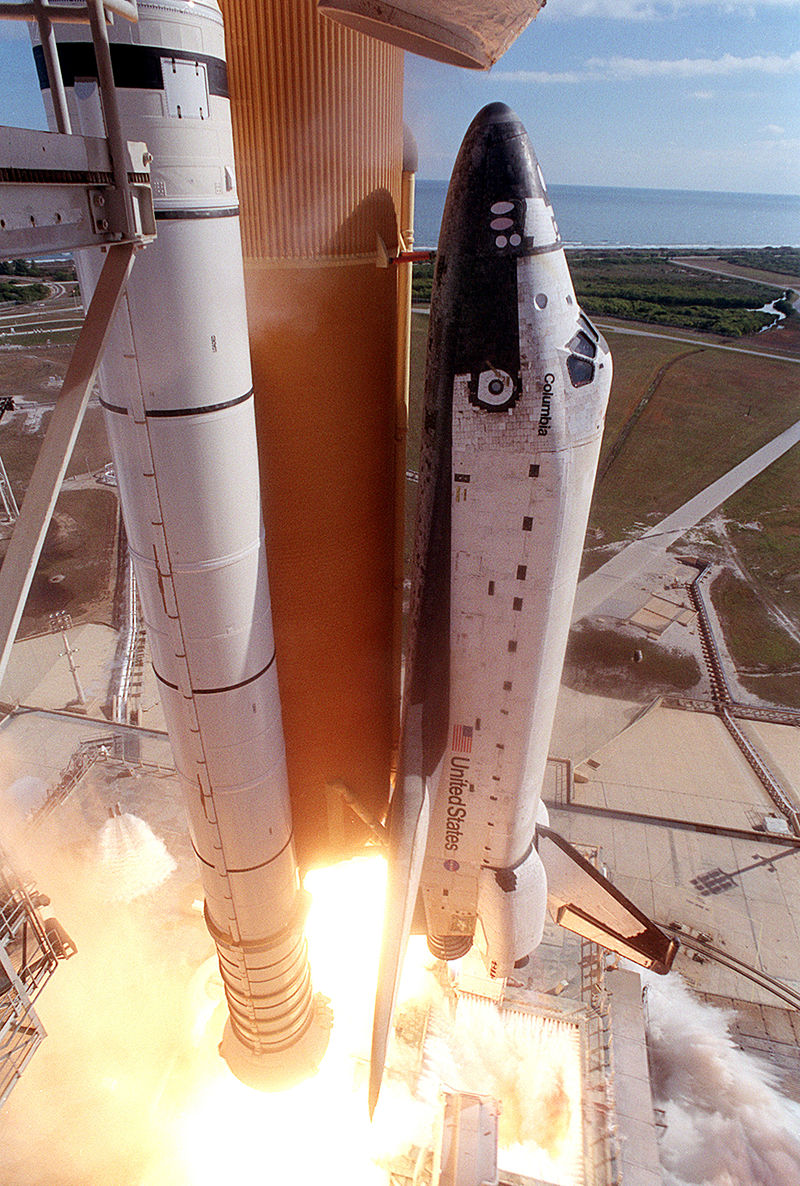

Launch of the Columbia: